Back in May, i went to Athens on a whim. Of course, Greece has the most fabulous food on the old continent, firemen on motorbikes, soldiers wearing pompom shoes, and jaw-dropping architecture. But I also wanted to see The System of Systems, a group show that explored how political powers are using technologies in bureaucratic systems to determine the fate of asylum seekers in Europe.

What better place than Greece to discuss this topic? Not only has the country developed an intimate experience of the EU brutal bureaucracy since the early days of the financial crisis, it is now also attempting to aid the thousands asylum seekers and refugees who have reached its frontiers in the hope of finding a better life in European countries. Unfortunately, like other member states on the EU’s external borders, Greece is receiving insufficient signs of solidarity from the EU.

Image Danae Papazymouri

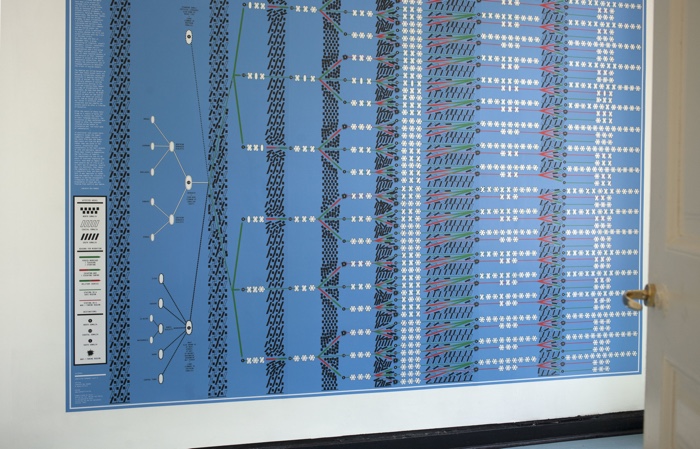

Danae Papazymouri & Rebecca Glyn-Blanco, And if the asylum seeker does not wish to participate in the interview? Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

The System of Systems looks at asylum seeking in Europe under a broader perspective. It is not only an exhibition but also a book and a series of events that aim to raise a better informed debate around the legal framework of asylum seeking in Europe, asking questions such as:

What policies are we voting for as citizens of European countries, and what is our relationship to this issue? How does the asylum system illegalise people? How are technologies used as processes of making and discrediting evidence?

The System of Systems ironically takes its title from an informal term used to describe EUROSUR, a division within border management agency Frontex. This subsection is an ‘information exchange framework’ and ‘surveillance system’ that operates on behalf of the EU. The process of seeking asylum is thus a ‘system’ composed of many ‘systems’. The rather clinical description suggests a number of rules and control apparatus but it also hides a series of complex and often harsh control mechanisms.

The System of Systems exhibition dissected the strategies used by the EU to ‘process’ and restrict the movements of people who don’t have the ‘adequate’ documents. It also examined the stratagems deployed by migrants to counter EU bureaucracy and enter “Fortress Europe.”

The show in Athens closed a few weeks ago. Other events are planned but in the meantime, i’d really recommend that you check out the publication of the project. Just like the exhibition, the book goes beyond the facts and stats you can read in the press and offers a more compassionate perspective on the asylum seeking process.

Here’s a quick tour of some of the works exhibited in Athens:

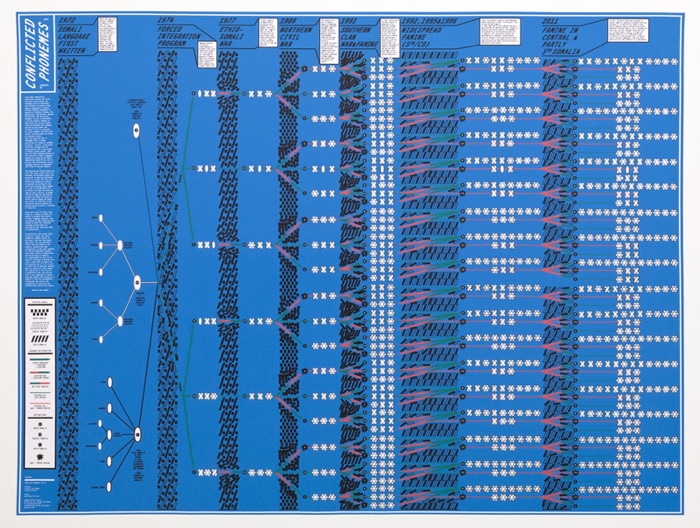

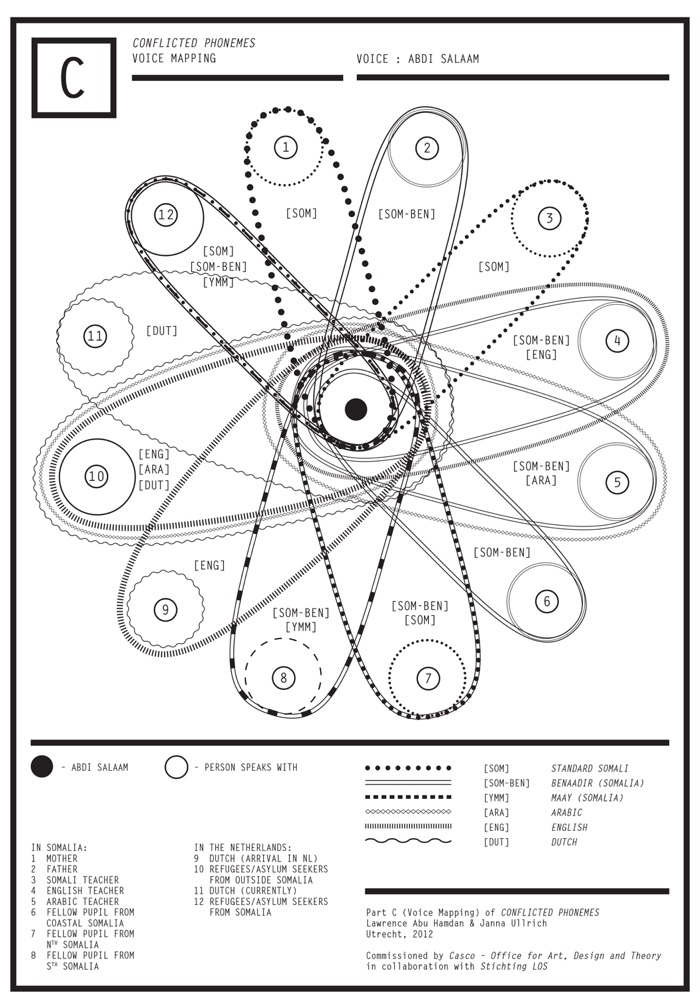

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Conflicted Phonemes, 2012

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Conflicted Phonemes, 2012

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Conflicted Phonemes, 2012. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Since 2001, immigration authorities in Australia, New Zealand, as well as several European countries have been using forensic speech analysis to determine the validity of asylum claims made by thousands of people without identity documents.

While applicants are interviewed, their language, dialect or accent are scrutinized by language experts who then assess whether or not the way the applicant speaks matches the one used in the region they claim to come from.

Forensic speech analysis is far from being fail-proof, however. This can have disastrous consequences for the fate of asylum seekers whose application has been unjustly rejected.

In 2012, artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan worked with linguists, artists, researchers, activists and twelve asylum seekers whose applications had been rejected following a language assessment. Together they discussed how to raise awareness around the limits of forensic language and worked with graphic designer Janna Ullrich to create a series of maps that expose the realities of this technology. The maps demonstrate that a spoken language is not a static entity but an hybrid, living organism that quietly evolves with changing social conditions, with age or under the influence of crisis and displacements.

The maps have been exhibited in galleries and refugee organizations, but they have also been presented to a judge working within the Dutch immigration authority. The research was also submitted at a deportation hearing before the UK Asylum tribunal.

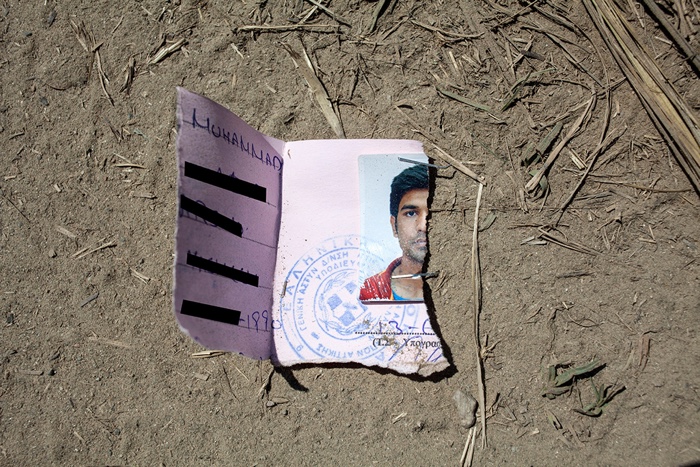

Eugenio Grosso, Papers, 2015

Eugenio Grosso, Papers, 2015

Eugenio Grosso, Papers, 2015. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Your documents don’t determine who you are—but they certainly have a lot to say about where you can go.

Eugenio Grosso photographed the papers left behind by those making their way through Europe in the hope of a better life. The photos were taken shortly before the controversial EU-Turkey deal which now allows Greece to return to Turkey “all new irregular migrants”.

Before the agreement, refugees allowed to enter Macedonia from Greece had to pass by a track that leads to the small town of Gevgelija. The path, a limbo between Greek bureaucracy and Macedonian bureaucracy, was where migrants tore apart and discarded the documents temporarily issued by Greece. Knowing their nationality could determine whether they would be allowed to continue their journey freely or be sent back or incarcerated, these men and women chose to leave part of who they were behind them. Each time they entered a new country, their identities had to be confirmed again and again.

Ayesha Hameed, A Rough History (of the destruction of fingerprints), 2015–2016. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

A Rough History reveals other sacrifices that migrants are ready to make in order to be able to enter the EU. Ayesha Hameed‘s film essay and performance explores how some of them are cutting or burning their fingerprints to avoid being identified by the EU’s fingerprint database, Eurodac.

Nana Varveropoulou, No Man’s Land. Each room in the category B prison holds two men

Nana Varveropoulou, No Man’s Land

Nana Varveropoulou, No Man’s Land

Nana Varveropoulou, No Man’s Land. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

The Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre was built as a prison. Yet none of the 380 detainees held there is serving a prison sentence. Most don’t even know when they will be released. Like other thousands of people locked in similar centers, they can be detained for months, even years. UK doesn’t accept them and the country they come from doesn’t recognize them. They can’t leave nor go, they live in a state of limbo.

During 2 years, Nana Varveropoulou worked with asylum seekers detained in Colnbrook IRC. She invited them to participate to photography workshops, gave them cameras and soon they started recording their life in the centre. In parallel, she produced her own photographs. Together, the detainees and the artist created ‘outsider’s’ and ‘insider’s’ perspectives of indefinite immigration detention.

Melanie Friend, Border Country. View of moat from Dover Immigration Removal Centre, August 2005

Melanie Friend, Border Country. The Visitors’ Room, Tinsley House Immigration Removal Centre (near Gatwick), April 2004. (The single chairs on the left are for detainees; visitors sit opposite)

Melanie Friend, Border Country. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Photographer Melanie Friend spent four years documenting what the UK calls the ‘Immigration Removal Centres’ (IRC.)

She interviewed detainees, portrayed some of them and photographed the interiors and exteriors of eight centers. At least the parts she was allowed to photograph.

The recordings of the interviews are particularly moving. We hear the voices of people who have no home nor belonging, are separated from their family and find themselves in a system they don’t fully comprehend. Some of them have been detained for months, waiting for deportation or asylum. Through they stories you get a sense of who they are, what they tried to escape, what they dream of and the psychological and emotional impact that life in this type of prison-like institutions has on them.

The photos only confirm the sense of confinement and alienation they have to face day after day for indeterminate periods of time: the high fences, the barbed wires, bright lights, security cameras, bleak rooms, lack of privacy, bars on the window, etc. Together, recordings and photos challenge the dominant representations of asylum seekers and migrants as ‘others’.

James Bridle, Seamless Transitions

James Bridle, Seamless TransitionsExhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

James Bridle, Seamless Transitions. The interior of Inflite Jet Centre. Photograph: Picture Plane/The interior of Inflite Jet Centre

James Bridle discussing Seamless Transitions at the opening of The System of Systems

It is illegal to photograph the detention centres, closed courts, lounges and private jets Britain uses to deport people. But James Bridle found a way around the restrictions. His work Seamless Transitions focuses on 3 key elements of the UK immigration system: a courtroom, a detention centre and an airport.

Field House in the City of London is the home of the Special Immigration Appeals Commission (SIAC), Harmondsworth IRC is a detention center near Heathrow Airport Heathrow and the Inflite Jet Centre is a luxury terminal at Stansted airport where businessmen check in for their private jets by day and deportation flights depart at night.

Since he had limited to no access to these spaces, Bridle had to acquire planning documents and satellite photos, interview academics and activists, and read accounts from eyewitnesses. He then worked with digital imaging studio Picture Plane to recreate the places as 3D computer models.

The film walks us through sanitized and empty environments. The work helps us visualize a reality that remains hidden. And while the images can’t convey the smell, the stress and despair these walls witness on a daily basis, they speak volumes of the lack of humanity and compassion of our immigration systems.

It’s about the unaccountability and ungraspability of vast, complex systems: of nation-wide architectures, accumulations of laws and legal processes, infrastructures of intent and prejudice, and structural inequalities of experience and understanding. Through journalistic investigation, academic research, artistic impression, and, I believe, the confluence of these approaches with new technologies, there is an opportunity to see, describe, and communicate the world in ways which have not been possible before, Bridle writes

More images from the show:

Design Unlikely Futures. Exhibition view The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Thomas Keenan & Sohrab Mohebbi, EUROSUR. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Thomas Keenan & Sohrab Mohebbi, It’s obvious from the map. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Conflicted Phonemes, 2012. Exhibition view of The System of Systems at GRACE in Athens

The System of Systems is a series of exhibitions, events and a publication curated by Rebecca Glyn-Blanco, Maria McLintock and Danae Papazymouri.