Two weeks ago, I was in Rome to see the Quadriennale d’arte (entrance is free and that’s the most positive comment I’m prepared to write about the show) and Re:Humanism, an exhibition that explored the relationships between art and artificial intelligence.

Re:Humanism is an art prize for artists whose work critically investigates the impacts that AI technologies are having on culture, aesthetics and society. This year’s edition of the event subtitled “Re: define the boundaries”, looked at how we can overcome an anthropocentrism that prevents us from questioning traditional ideas about what constitutes life, consciousness and intelligence. The artists in the exhibition shift these boundaries by playing with machine learning, robotics and computer vision of course but also by challenging the idea of a presumed hierarchy that places our species over everything (everyone?) else. Be it organic or algorithmic.

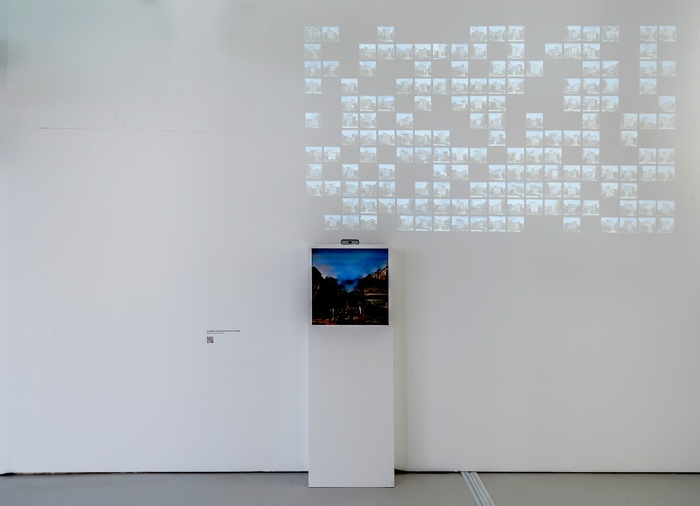

There were 10 artworks exhibited in a clinical and impersonal setting. As if AI were all about tech and had no connection with life. Some of the works were fairly interesting though. With Three Thousand Tigers being the real gem in the show.

Irene Fenara, Three Thousand Tigers (detail), 2020, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and UNA Galleria. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Irene Fenara, Three Thousand Tigers (detail), 2020, exhibition view. Courtesy of the artist and UNA Galleria. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Irene Fenara, Three Thousand Tigers (detail), 2020

Irene Fenara, Three Thousand Tigers, 1017, 2020. Photo: Andreas Manini

According to the WWF, there are more tigers in captivity in the United States than in the wild around the world. An estimated 3,900 tigers remain in the wild. Yet, the images of the endangered feline are everywhere we look: on sweatshirts, on cereal boxes, in cartoons, on the logo of restaurants, of sports teams, etc. And on tv of course.

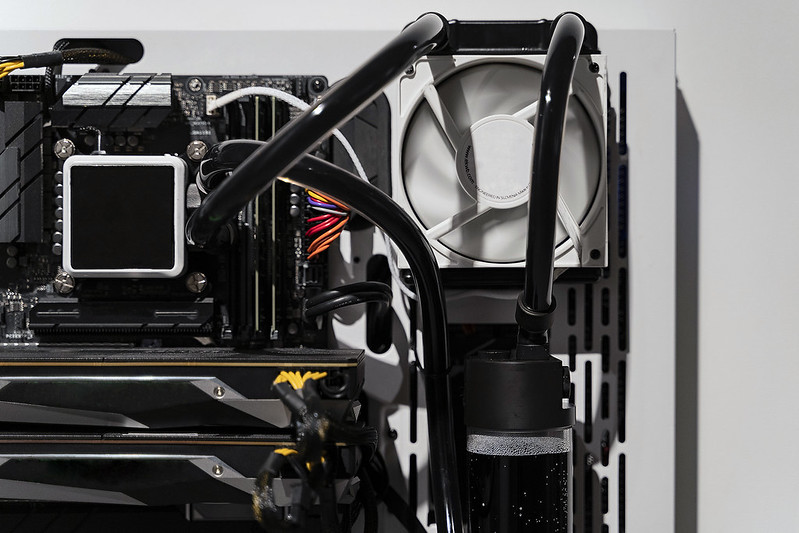

Irene Fenara fed 3000 images of tigers to an algorithm that started generating more images of the endangered feline. Such meager dataset makes it difficult -if not impossible- for a generative algorithm to identify and create new tigers. The algorithm only managed to preserve some characteristics of the original animal. Mostly abstract patterns that evoke the fur of the formidable cat. The artist then had the patterns turned into carpets in India (where most tigers in the wild live.)

Three Thousand Tigers establishes parallels between biodiversity erosion and the kind of digital deterioration that happens when files lose quality with each upgrade of computers and software.

Irene Fenara goes even further in an interview with ATP Diary: “On the one hand I was interested in the analogy with animal skins that are used as carpets. On the other, I wanted to underline that weaving works a bit like an algorithm. The weave and warp of the fabric move in a similar way to the sequences of computing code.”

One of the main reasons why I liked this work so much is its quiet demonstration that, in spite of technology developers’ promises, AI cannot solve all the problems related to environmental degradation. Another reason for my enthusiasm is its tactile, organic dimension. You don’t need to throw sensors and screens at visitors to make valid comments about AI technology.

Numero Cromatico, Epitaphs for the Human Artist, 2021. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Numero Cromatico, Epitaphs for the Human Artist, 2021. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

In Epitaphs for the Human Artist, a neural network was trained using poetic words and expressions often found in epitaphs, the short texts honouring a deceased person. You can guess what happened next: the system generated its own obituaries. Often abstruse and without referent nor emotion, the formulas only highlight the clichés of the genre.

The work hints at the upcoming obsolescence of writers and other human creators within a society that is increasingly delegating cognitive tasks to machines.

Egor Kraft, Chinese Ink, 2019

Egor Kraft, Chinese Ink, 2019. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Chinese Ink displays real-time outputs of an AI system on electronic ink screens. The system, trained on a dataset of nearly a thousand blots of Chinese ink splashed onto calligraphic paper, generates a dozen of similar images per second. They are as inimitable and seemingly as random as the original set. Their succession on the displays also recalls the effect of ink spreading on blotting paper.

Kraft’s focus is less on the iconographic subjects than on the properties and materials used in traditional Chinese ink painting techniques. Electronic ink displays and developments in machine learning are fields China is mastering. Just like the country excelled at traditional calligraphy. The experiment thus invites the public to reflect upon how ancient crafts, visual languages or artforms survive and change with the advancement of technological progress.

Yuguang Zhang, (Non-)Human: The Moving Bedsheet, 2020. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Yuguang Zhang, (Non-)Human: The Moving Bedsheet, 2020

Yuguang Zhang, (Non-)Human: The Moving Bedsheet, 2020

Yuguang Zhang’s kinetic AI installation (Non-)Human: The Moving Bedsheet invites AI to enter our most intimate moments and objects. Using a dataset of images of the poses he had adopted during sleep, the artist trained a neural network to generate further movements and then transmit them directly onto bedsheets. The work suggests a world where the human manifests itself in non-human forms. There’s something disturbing and invasive about a non-human entity that probes and imitates the unconscious gestures we make when we are asleep.

More images from the show:

Carola Bonfili, The Flute Singing, 2021

Mariagrazia Pontorno, Super Hu.Fo* Voynich, 2021, exhibition view. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Entangled Others Studio and Sofia Crespo, Beneath the Neural Waves 2.0, 2021

Entangled Others Studio and Sofia Crespo, Beneath the Neural Waves 2.0, 2021, exhibition view. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism

Elizabeth Christoforetti and Romy El Sayah, Body as Building

Elizabeth Christoforetti and Romy El Sayah, Body as Building, exhibition view. Photo by Sebastiano Luciano for Re:Humanism