The drastic drop in biodiversity. The deforestation in the Amazon and the acidification of the oceans, the melting glaciers and the microplastics inside babies, the sea level rises and the reduced fertility of the soils. We know about all these tragedies because we have seen the graphs and images on our computer screens. And we know exactly how bad these phenomena are because we surround ourselves with machines that scrutinise, measure and “decode” the living world for us.

Postcoïtum concert at Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles, an art festival that took place in late June in Marseille, presented the work of artists who explore “the metabolic exchanges” between humans and their environments. Some of the works selected observe how other cultures have managed, far better than we do, to never forget that humans cannot be fully alienated from the living. Other pieces attempt to formulate new strategies to connect to other animals, plants, rocks, to atmospheric phenomena even. Together, they probe into the effects that this (very Western) estrangement is having on the biological and spiritual exchanges between humans and ecosystems.

Métaboles seemed to resonate with the broad public. I not only saw the usual crowd of culture addicts, I also saw groups of children, families and passersby living in the neighbourhood. It probably worked because the event never tried to be didactic and prescriptive. Or because its programme mixed debates, beers, screenings, sound performances, conversations in the sun and art installations. It was poetic and it was fun. There were tajines and food for thought. A great formula to start difficult questionings.

Here’s a tour of some of the works and moments I found most interesting:

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021. Photo by Luce Moreau

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021. Photo by Luce Moreau

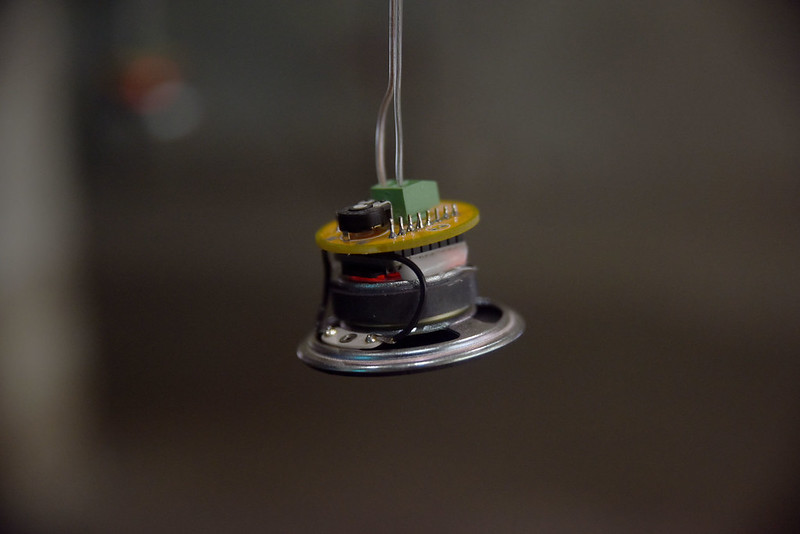

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021. Photo by Luce Moreau

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021. Photo by Luce Moreau

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021

Félix Blume, Essaim/Swarm, 2021

The Essaim/Swarm sound installation is composed by 250 small speakers, each one reproducing the sound of an individual flying bee. The artist recorded the flying bees using a sound recording studio specifically designed for them. When you approach the installation, you can hear the sound of the whole swarm. By getting closer, however, you become part of the swarm. You are immersed in the buzzing sound but can detect the individual “voices” of the tiny insects.

I’m always a bit suspicious of the need to use technology to appreciate nature but since I’m not planning to shove my head inside a swarm any time soon, I must say that the installation worked for me. The soothing sound, the visually mesmerising sculpture… Pretty much anyone who entered the space was immediately drawn to it.

Luce Moreau, Brèches mécaniques. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Luce Moreau, Brèches mécaniques. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

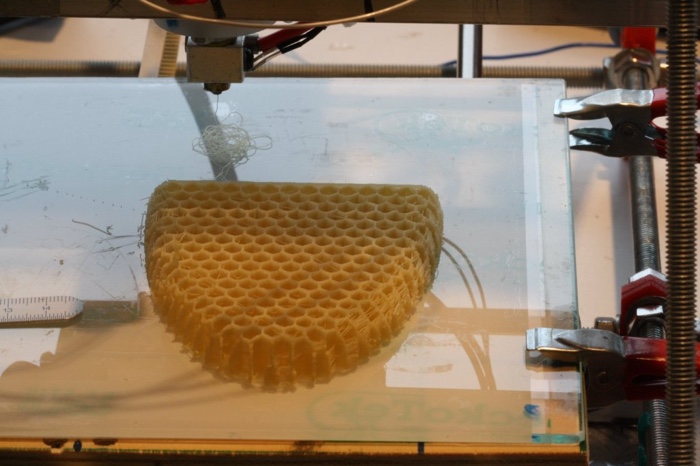

Luce Moreau, Brèches mécaniques. © Luce Moreau

Brèches mécaniques by Luce Moreau is a honeycomb made of bees wax but 3D printed by humans. Placed on the ceiling of the exhibition space, the piece quietly awaited to be discovered, appropriated and customised by bees as their new home. The human artist offers the basis of a home and the insects then decide if and how they should inhabit it.

The trans-species collaboration shifts the border between what is natural and what is artificial but it also highlights the close interconnectedness between humans and pollinators. We rely on them for food. They rely on us not to destroy the wildlife where they thrive. Moreau’s artwork echoes the preoccupations of other French citizens who are active in campaigning against the widespread use of chemicals that harm wildlife and decimate crop-pollinating bees.

Alexandre Chanoine, Sculptures & sound performance, 2021. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Alexandre Chanoine, Sculptures & sound performance, 2021. Photo by Luce Moreau

Alexandre Chanoine, Sculptures & sound performance

Alexandre Chanoine, Sculptures & sound performance, 2021. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Alexandre Chanoine, Sculptures & sound performance, recorded in his studio in 2017

Alexandre Chanoine manipulates stones and turns them into sculptures and musical instruments.

Back in 2010, the artist discovered the graining of stones in the lithography studio of a fine arts institution in Nantes. Once a stone has been printed from too many times, it is necessary to “re-grain” it by removing the greasy layer, exposing the unprocessed stone underneath and enabling the stone to be re-used. That’s when Chanoine discovered that stones could produce primitive and harmonic sounds.

From that moment, his stone sculptures would also become instruments that create sound pieces. His performances look physically demanding. With each gesture of pushing and pulling, turning, shaking, scratching, eroding and dragging, the artist releases some of the many layers of time enclosed within the mineral matter.

Špela Petrič, Skotopoiesis. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

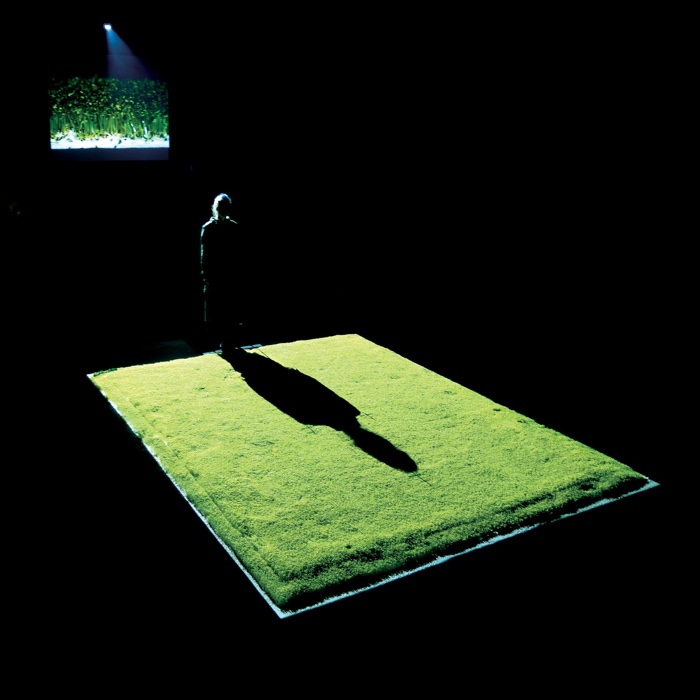

Špela Petrič, Skotopoiesis

Špela Petrič was showing a video of her iconic performance Skotopoiesis. Part of the series titled Confronting Vegetal Otherness which challenges the anthropocentric approach to the vegetal world, Skotopoiesis (meaning shaped by darkness) is an attempt to establish a more egalitarian relationship with plants.

For nineteen hours, Petrič stood still and cast her shadow onto a garden of cress. By obstructing the light, the artist stimulated the production of auxin, a group of plant hormones that regulate growth and cause stems to lengthen. The cress plants that grew under Petrič’s shadow were thus whiter and more elongated that the others. The artist not only experienced time from a plant perspective, she was also physically affected by the encounter: while the cress morphologically changed, the artist also did, her body temporarily shrank as a prolonged standing position caused her backbone to shorten.

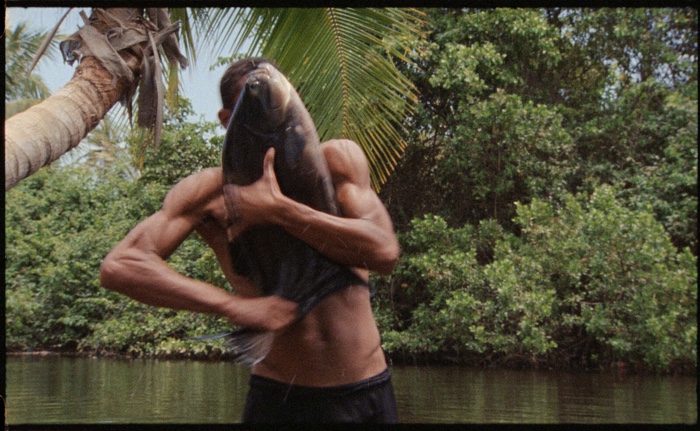

Jonathas de Andrade, O Peixe (The Fish), 2016

Jonathas de Andrade, O Peixe (The Fish), 2016

A programme of evening screenings (I already wrote about Paparuda, Maxime Berthou’s investigation into cloud-seeding) accompanied the exhibition. I’ll only mention a couple of them:

O Peixe (The Fish) follows the fishermen of villages on the Northeast coast of Brazil as they enact a ritual of embracing the fish they have just caught. The animal gasps for air and dies in the arms of its predator. The gesture is ambiguous: it speaks of gratefulness but also of violence and domination.

I found the images unbearable. The atmosphere is peaceful, the natural surroundings are stunning but, to a westerner like me, the hug evokes both sheer brutality and maybe also a desire to connect to the species we live from. There is something lucid and honest in that gesture, it is so remote from what happens in societies like ours, where the killing of the animals we eat happens on a massive scale, behind closed doors and is delegated to poorly paid people. Another difference is that unlike the fishermen in the Brazilian village, our daily survival doesn’t depend on the killing of animals.

“The fish is about the collapse of the relationship between man and nature, but also about working, surviving,” de Andrade says. “And it’s about a village that lives in harmony with the environment, asking permission. Nonetheless, it is a fatal hug, one of domination. In terms of the Anthropocene, it becomes a metaphor for the total failure to limit exploitation, the normalization of killing, unbounded consumerism, self-serving environmental devastation. But the image could also be read as a simple idea of surviving on this planet.”

Felix Blume, Curupira, creature of the woods (trailer), 2018

Felix Blume, Curupira, creature of the woods, 2018

Felix Blume presenting his work at Métaboles. Photo by Luce Moreau

Felix Blume traveled deep into the Amazon forest where inhabitants of the Tauary village told him about a creature hiding among the trees. Some of them have heard her. They say her voice is not human but neither is it like the one of any other animals. Very few have seen her, and those who did find her never came back. Her name is Curupira and her story lives on in the oral memory of the villagers. Felix Blume uses sound as an instrument to look for a creature that escapes human eyes. His recording acts both as an invitation to listen to the sounds of the jungle and the animals that inhabit it and as an instrument to reveal other means of gathering knowledge and to investigate the place of myth in today’s world.

More images from the event:

Performance at Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles. Photo by Luce Moreau

Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Performance at Métaboles. Photo by Luce Moreau

Métaboles. Photo by Florent Kolandjian

Métaboles is a co-productions of Les Ateliers Jeanne Barret, 1979, DDA Contemporary Art, M2F Créations|Lab GAMERZ and OTTO-Prod. The event took place at Les Ateliers Jeanne Barret, a cultural space named after an 18th century explorer and botanist, the first woman to have, disguised as a man, completed a voyage of circumnavigation of the globe.

Previously: Who owns the clouds and the water they contain?