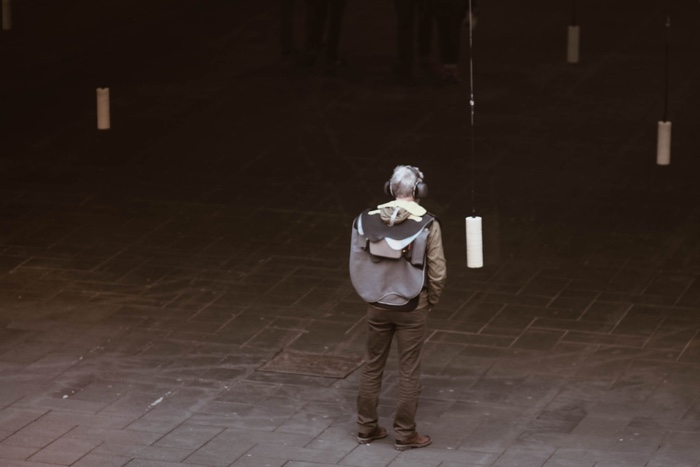

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: ©Joeri Thiry, STUK

The province of Groningen in The Netherlands has the largest gas field in Europe. Since the early days of extraction in 1959, the field has produced billions of cubic meters of the natural resource. The exploitation is a lucrative business but, because the extraction process is causing earthquakes, it is also ruining the lives of the local residents. Many of the houses in the area have been so badly damaged by the man-induced earthquakes that they are uninhabitable.

Gas field in Groningen. Photograph: Jasper Juinen/Bloomberg/Getty Images, via The Guardian

House in Groningen. Image via CBS

Sissel Marie Tonn‘s artwork The Intimate Earthquake Archive is an attempt to understand and communicate the psychosomatic effects that these man-made seisms have on the people who live in the area. The research behind the installation combined an exploration of the vast amount of data available in scientific archives (from core samples to sand and soil lab tests, to data on seismic activity recorded by the Dutch Meteorological Institute or KNMI) with a collection of the personal stories told by the inhabitants of Groningen, who describe how they feel the earthquakes passing through their bodies and homes.

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: ©Joeri Thiry, STUK

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: ©Joeri Thiry, STUK

The artist collaborated with sound artist/composer Jonathan Reus to turn the digital siesmic archive of the KNMI into a tactile archive, one which can be physically accessed and experienced by the visitor through their body when they don a specially-designed waistcoat with embedded surface (skin) and bone conduction transducers.

The artists have selected 12 earthquakes of cultural and political significance to be part of this sensory archive, and have worked to transform these data sets into vibratory compositions that move across the body and at the subsurface of the skeleton, producing a composition of tremors on the surface of the body – in the same way the seismic waves move across the land.

The Intimate Earthquake Archive is not only an interactive installation that invites “deep listening” within the body but also a reflection on how anthropocentric geological changes might be recorded, experienced and how they can be reproduced for other people in order to help them attune themselves to a future marked by man-made geological changes.

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive, 2017. Video by Tanja Busking

I was supposed to go and experience the work back in February when it was exhibited at STUK in Leuven (Belgium) during the Artefact festival. Unfortunately, one of the joys of the winter was that i got very ill and had to cancel the trip. My only consolation was that Sissel Marie Tonn has kindly agreed to be interviewed about her project:

Hi Sissel! The The Intimate Earthquake Archive started with a research into the blurring between nature and culture in The Netherlands. What is so special about it in the country? Could you give a few examples?

I guess I believe that the scale of anthropocentric modifications of the biosphere has made this separation between nature and culture somewhat impossible. What I find interesting living in The Netherlands is how land management and stewardship is so integral to the Dutch cultural history and mentality.

When researching the phenomenon of the man-nmade earthquakes in Groningen I also started looking into the peat industry in the country, emerging in the 11th century, up until around the 1960s. Peat is is an accumulation of partially decayed vegetation and other organic matter that can be used as fuel, and the extraction methods of peat was eerily similar to the mining of fossil fuels today. When the reserves most easily accessed had been exhausted peat diggers developed new methods and technologies to reach further into the bogs and mires. This industry has left a visible mark on the landscape, where some areas look like thin-toothed combs of land strips cutting through the water-filled bogs. The peat industry has made it into the cultural history of the country as well – from social history of the poverty of the peat diggers, to developments of canals to distribute the peat, to museums, street names and archives commemorating this use of the land, and the benefits and repercussions it had on culture and life in general. Looking at this part of history I became interested in the idea of how the gas-induced earthquakes that have taken place in the province of Groningen since the mid 80s would enter into Dutch cultural history as a form of archive as well.

I had a look at this phenomenon of man-made earthquake and at the protests of the local population. From what i could read online, it’s very damaging for the houses. But you are more interested in the intricacies between nature and culture of course.

Could you explain the impact these earthquake are having on the human body of course but also maybe (if this has been documented) on the environment in general?

The starting point for this research was a curiosity towards how living with man-made ecological change changed one’s perceptions of place. I had a hunch that experiencing subtle or profound changes within ones immediate environment somehow amplified a sense of a presence of that space, giving an opportunity to grasp the interconnectedness between body and surroundings. This was something I had been working on for a while, but in 2015 I heard about this strange phenomenon – man-made earthquakes. I got in contact with some people who were living in the town where the gas was first discovered in the 60s – really lovely people that hosted me while being there.

I became interested in how they described the earthquakes: physical sensations, metaphors describing how they sounded and felt, as well as the stories they told of dealing with the bureaucracy around damage claims towards the NAM (Dutch earth gas company), the feeling of being ignored by the state and politicians for decades, and the anxiety of not knowing what could happen. The aspect of uncertainty connected with the phenomenon, and the fact that the scientifically predicted “highest magnitude” has changed (and is, essentially, impossible to calculate) brings quite a lot of anxiety and fear to the people living in this area.

I was interested in how some people claimed to wake up seconds before an earthquake was felt. To me this shows a tangible relationship between what philosopher Felix Guattari calls the interconnection between the ‘social’, the ‘mental’ and the environmental ecologies. Guattari stated in his essay ’Three Ecologies’ already in ’86 that we would never be able to solve the ecological crisis without addressing these other ‘ecologies’, and I find that very interesting in the context of the man-made earthquakes. When people feel neglected by the state and industry it is as if they develop bodily attunements towards these changes – almost as a mode of survival. At around the same time I was also visiting various governmental institutes that were gathering information on the phenomenon – a huge warehouse full of all the core samples that have ever been taken from the ground, laboratories researching new opportunities for extraction of the material samples from the earth, and the seismologists working on the huge digital database of all the seismic activity recorded in the area. These very different encounters sparked the idea of creating the Intimate Earthquake Archive.

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view at Artefact festival, STUK. Photo: Photo: Kristof Vrancken

How did you recreate the feeling of earthquake on bodies? Did you work with people living in the area to have feedback on how close the sensations are compared to what they feel?

The Intimate Earthquake Archive is not an attempt to recreate the feeling of an earthquake per se – it’s not an earthquake simulator. It is rather the gesture of taking a digital seismic archive (managed by the Dutch Meteorological Institute and which can be accessed here) and bringing it into the realm of the sensing body – to create an opportunity to know about this phenomenon through the body (rather than the overwhelming amount of scientific information already gathered). I found it interesting that the meteorological institute had made this archive public, yet the data one can retrieve on there is very abstract to someone without specialised knowledge.

Together with sound artist Jonathan Reus, as well as with Marije Baalman and Carsten Tonn-Petersen, who did electronics/software development, I created The Intimate Earthquake Archive, which connects the digital seismic archive of the man-made earthquakes in Groningen with the sensing body of the visitor. We have designed a wearable interface with embedded surface (skin) and bone conduction transducers.

We have chosen 12 earthquakes of cultural and political significance to be part of this sensory archive, and have transformed these archival data sets into vibratory compositions that move across the body and at the subsurface of the skeleton. Visitors choose which earthquake compositions they want to experience by positioning themselves within a network of long-wave radio transmitting core samples, where proximity to the samples increases the intensity of experiencing that entry. The vibrations move across the skin similarly to how the earthquakes moved across the land, and are intended to inspire a ‘deep listening’ experience within the body.

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

Sissel Marie Tonn, The Intimate Earthquake Archive. Installation view STUK. Photo: Kristof Vrancken

What do visitors experience exactly? What are the sensations on the body like? How strong or unpleasant is the feeling?

The visitors put on the vests, as well as noise cancelling ear protection muffs. Then they enter the installation where, as they approach different core samples, compositions of vibrations play out on their bodies. The transducers are distributed so that there’s a mixture of vibration of the skin through parts of the body, and direct transduction of sound through the bones at other parts of the body. So what they feel is a composition for these different modes of experience, based on the seismic recordings, which communicates information on how the earth was vibrating along the x, y and z directions (measured at stations at multiple distances from the epicentre of the earthquakes). The compositions take advantage of the multiple types of vibrations that the vests allow the visitors to feel. For example with bone-conduction you have the sensation of sound coming from within the body, and from no particular direction, whereas with haptic transduction of the skin, it’s really a tactile experience. These different dimensions combine to create a kind of deep listening experience that’s internalised through the body, and this experience is strengthened by the earphones that block out all other environmental sound.

Did you manage to answer the question mentioned in the description of your work “is the sensation of a man-made earthquake fundamentally different than the sensation of a natural one?”

First of all I think there is just something fundamentally weird about the whole concept of ‘man-made earthquakes’. Earthquakes is often connected with the ‘force’ of nature, something outside of our control. But now to a larger and larger degree humans have the capacity to act as geological agents. Therefore I think there is something jarring to the experience of an earthquake that is produced by our dependence on fossil fuels. Furthermore, as I mentioned earlier, the occurrence of these earthquakes are entwined in mistrust toward the government and industry, resulting from years of neglect and the feeling of being silenced to protect industry, as well as the anxiety of the unknown. These social and mental factors play into the experience of an environmental change that is anthropogenic, and needs to be taken into consideration.

I’m quite curious about the core samples made of sand stone that hang over the head of the audience. Why did you use sand stone?

I used sandstone because this is the kind of stone where the gas is found. I liked the idea that these hanging objects in a way represent the beginning and the end of the phenomenon (core samples being drilled to research whether that particular sedimentary strata contains gas, and the earthquake resulting from the drilling). The samples are kindly donated to us by the TNO (The Geological Survey of The Netherlands). We have been very lucky to get help and information from a lot of scientists working on the phenomenon in The Netherlands.

Why is it more important to you to transfer a physical experience rather than provide information about the phenomenon?

I am interested in moments where relations between our body and the environment around us are revealed to us, and perhaps make us more aware of our place in and effect on the earth system. I am particularly fascinated by how evolutionary processes, such as our senses and perceptual modes of attention, affect our ability to perceive environmental changes, and thereby affect our capacity to act upon them. In that sense I think it’s important to move away a bit from the more cerebral aspects of dealing with the issue of man-made ecological change. Therefore I often create wearable ‘tools’ that challenge the body’s preconfigured modes of perception, for instance by amplifying signals of environmental changes that slip below the radar of our senses, or which exist in a time other than the present. I am interested in how these ‘tools’ can create an awareness of the reciprocal relationship between the body and the surrounding environment, as well as question how artifacts, forms of knowledge, and architecture, shape our perception of the environment. What can we take from these situations, where people living with man-made ecological changes start relying more on the senses of their own bodies than that of scientific measurement systems? I am interested in implicating the body of the visitor, of showing that these changes (in the larger picture) will fundamentally affect the body, and perhaps that we need to attune our bodies more towards these changes in order to act upon them.

Sissel Marie Tonn and Jonathan Reus, Sensory Cartographies, 2016 – ongoing

Sissel Marie Tonn and Jonathan Reus, Sensory Cartographies, 2016 – ongoing

You designed The Intimate Earthquake Archive as “a kind of test ground for the visitor to attune herself to a future marked by man-made geological change.” Is this something you are interested in pursuing beyond TIEA? And which kind of other man-made geological change do you think you should brace ourselves for?

I am working with sound artist Jonathan Reus on an ongoing research-based project called Sensory Cartographies, in which we develop worn biometric and body-extension instruments that challenge the body’s pre-conditioned modes of paying attention. We see them as way-finding apparatuses for reshaping a worldview – knowing momentarily without focus – creating an alternative cartography that is attentive to subtle fluctuations of change.

Sissel Marie Tonn (in collaboration with Studio van Broekhoven for 3D design), Becoming Escargotapien at the Jan van Eyck Open Studios in Maastricht. Image courtesy of the artist

Sissel Marie Tonn (in collaboration with Studio van Broekhoven for 3D design), Becoming Escargotapien at the Jan van Eyck Open Studios in Maastricht. Image courtesy of the artist

You have recently installed another of your artworks, Becoming Escargotapien at the Jan van Eyck Open Studios in Maastricht. What is the project about?

Becoming Escargotapien is a project I started last year. It deals with the many ways in which the human body is fundamentally entangled with the surrounding world. Living in a world where bi-products of industry seep into our bodies, where ocean acidification bleaches coral reefs and perforates the shells of mollusks, and plastics make it back into our bodies. It seems urgent to me to think about what power-laden distinctions we draw between nature and culture (as we talked about earlier), but also between human and non-human, and between body and environment in general. The Escargotapien is a speculative species I have invented, a kind of tool to explore these distinctions through a story.

The installation that I set up at Jan van Eyck consists of a spoken ‘tale’ that connects the developments of calcified matter in organisms during the Cambrian Explosion with contemporary use of 3d printing technologies used in regenerative medicine. Specifically, it deals with the use of mother-of-pearl as material for reconstructing human bone: Some 550 million years ago, when the oceans underwent a sudden mineralization, the soft organisms of these ancient waters started developing spinal cords and exoskeletons. From then on, species developed along separate paths. But something in the body still recalls this shared past, making this marriage of bone and nacre (mother-of-pearl) possible today – bone doesn’t easily forget its mineral origins. Similarly, fossils of the deep past can reveal astounding facts about their environments through material traces embedded in the petrified bone.

The tale is told through a direct vibratory connection between the bone of the visitor and the 3d-printed ‘porosified’ fossil making up the listening devices (the sound is transmitted through a bone-conducting transducer). The tale almost becomes embedded into the body of the visitor, as a felt memory of vibration, that they take with them – for a while at least.

The installation also contained an architectural intervention into the studio space, where the floor was raised in order to bring visitors close to the windows. The movements of the outside world are thus brought into closer relation with the immersive experience of listening/being in the space. The soft ‘mat’ covering the platform requires the visitor to balance and move differently around the space, while being made aware of the repercussions of such small perceptual changes and repositioning of the body, through the audio.

Thanks Sissel!

The Intimate Earthquake Archive was at Artefact Festival, STUK, Leuven, BE and is shown again as part of Hyberobjects Exhibition which opens on 13 April at Ballroom Marfa, Marfa, TX, USA.